Iconic Cinematography: Our 5 Favorite Shots from Conrad Hall

One of the most respected and well-known cinematographers of all time, let’s take a closer look at what makes Conrad Hall’s work remarkable.

Conrad Hall‘s work as a cinematographer spans over four decades. He’s won three Oscars, and is one of the few cinematographers to have a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

Now, I know that the title of this article says “5 Favorite Shots,” but after re-watching many of Hall’s films, I had no choice but to select more than five. So, instead, I’ll be focusing on multiple shots and/or sequences from five of his films.

1. Road to Perdition

First, let’s get to the elephant in the room. Road to Perdition is a visual masterpiece. While watching it in the theater, I recall one scene in particular that made the audience audibly gasp.

At this particular moment in the film, young Michael Sullivan returns home to find a hitman (Daniel Craig) staring back at him through the window of the front doorway. Sullivan is stunned in terror staring back, sure that he’s in imminent danger.

When we cut to the reverse shot, however, we see that Daniel Craig is simply looking at his own reflection in the window. When he opens the door to leave, Michael has already ducked into the safety of darkness.

The final shot is a brilliant use of contrast to show both characters in the same frame. Michael’s face is outlined via the light from the house, while Daniel Craig is standing out against the faint outdoor light and the interior house light. The audience feels the danger.

The use of reflection, shadows, and contrast make this scene incredibly intense.

This illustrates Hall’s mastery of tonality, hearkening back to his early days shooting in black and white. In fact, Hall originally wanted to shoot Road to Perdition in B&W. However, in the end, they went with a high contrast look incorporating muted greens and browns.

Another reason this is so visually powerful? There’s no dialogue.

DIY: Pay attention to the background. Play around with mirrors to bounce light and creatively use reflections.

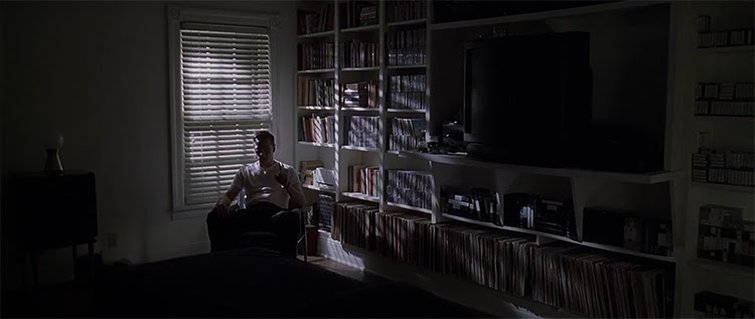

2. American Beauty

Back in the year 2000, I wore out my VHS copy of American Beauty from showing my friends all of my favorite shots. This film is full of amazing cinematography.

Two frames, in particular, stand out in my mind, and they both serve as perfect examples of how lighting can serve the story.

In this shot, Kevin Spacey’s Lester Burnham is fantasizing about his daughter’s new friend, the young and beautiful Angela Hayes (played by Mena Suvari). The soft lighting and haze add to the dreamy atmosphere. The blown out shaft of light coming in through the center window seem as if Lester is about to enter heaven.

In contrast, this particular shot has the same composition, yet it uses hard, direct lighting. This helps to communicate the harsh, threatening reality that young Ricky Fitts experiences. In this scene, Ricky’s father lies in wait to confront and discipline him. Certainly more dark and ominous than Lester’s fantasy.

DIY: Harness the power of haze and atmospheric aerosol to create some interesting looks.

3. Searching for Bobby Fischer

While many say that Road to Perdition is Hall’s best work, I would argue that Searching for Bobby Fischer is, in fact, his magnum opus.

In the early 90s and well into his career, Hall shot Searching for Bobby Fischer, the story of a young chess prodigy. According to Hall’s agent, many cinematographers turned down the opportunity to shoot this film as there were “not many visual opportunities.” Hall proved all of them wrong, winning an ASC award for his work.

My favorite aspect of this film is how a good majority of it was shot using close-ups. This might sound distracting, but it works incredibly well to suck you into the story. With a tight composition and extremely shallow depth of field, Hall helped show the small world view of the seven-year-old protagonist, as well as the pressures he faces throughout the film.

It’s also quite effective when shooting a chess board.

Hall captured the film in a style he dubbed “Magic Naturalism,” which essentially meant to shoot things as they are, while adding stylistic touches to heighten the atmosphere. This included blowing out the light coming through windows.

Another feature adding to the Magic Naturalism is the way the sunlight constantly dapples the actors. In both interior and exterior shots, you’ll rarely find a frame that looks flat.

How do you make a chess game look interesting? You hire Conrad Hall.

DIY: Don’t be afraid to blow out your backgrounds and use the edge of your light beam on an actor. Not everything needs perfect three-point lighting. Keep it simple. And, to get that shallow depth of field, shoot with your aperture as wide open as possible.

4. Cool Hand Luke

Did you know that Conrad Hall is actually the stepfather of J.J. Abrams? Okay, that’s actually not true, but it’s safe to say that he’s indeed the father of the modern lens flare.

Early on in his Hollywood career, Hall quickly became known for breaking established filmmaking rules. One thing in particular that gave him this reputation was his acceptance of lens flares. The flares work especially well in Cool Hand Luke.

In those days, a lens flare was considered a mistake, and film crews worked hard to avoid them. Hall, however, embraced the phenomenon, using the flares to help show the fierce heat the prisoners experienced working under the hot sun.

Hall is known for going with the flow and capitalizing on what many other cinematographers might consider to be mistakes or road blocks.

You should never work from a masterly sense, but from the sense of: Is this going to work or not? I still think that way.

-Conrad Hall

The flares are found throughout the film, not only with light from the sun. This added a little something extra to the rebellious tone of the film. Is there really a better time to break the rules than when shooting a film about breaking the rules? I think not.

If you pay attention, you’ll find flares throughout his work, including Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid.

DIY: Download these 17 FREE anamorphic lens flares for your next project. And, don’t forget to break the rules, kids.

5. In Cold Blood

If you’ve spent any time attending film school, you’ve probably heard about this shot. One of the most famous Conrad Hall images, the crying shot from In Cold Blood wasn’t actually planned out.

The scene shows Robert Blake in an emotionally tense moment, delivering his lines while standing next to a window. It’s raining outside, and a source light shines through the glass.

After lighting the scene, Hall noticed that the shadows of the water droplets were projecting onto Robert’s face, resembling tears. Not only was this an interesting look, but it significantly aided the story.

Hall mentioned it to Director Richard Brooks, and they successfully captured the shot. What further aided the scene was that Blake wasn’t actually crying, but rather playing the scene straight.

DIY: Experiment with putting objects between the light and your subjects. And, play around with projection.

For more on Conrad Hall, check out his use of the long shot.

Cover image via IMDb.

For additional cinematography tips and advice, check out these articles: